History

Many slaves brought the tradition of African outdoor ceremonies to the Caribbean. However, once enslaved, they were prohibited from holding public celebrations despite their slaveholders' engagement in street parades like Mardi Gras. Once freed, ex-slaves began their own street celebrations, combining elements of African and European culture. Costumes for these celebrations became larger and more spectacular as the parades became louder and wilder, infused with musical rhythms. As Caribbean people migrated to North America, they brought with them this new type of carnival.

During the 1920s in New York, a Trinidadian immigrant, Ms. Jesse Waddle, began to organize a carnival celebration to take place before Lent in the months of February or March. Due to New York's cold winter weather, these celebrations originally occurred indoors at places like the Savoy, the Renaissance, and the Audubon Ballroom. Eventually, the indoor locations became a problem because of their confinements on the movement and freedom that defined the carnival. Waddle applied for and received a street parade permit in the 1940s and shifted the celebrations to a warmer time of year, Labor Day.

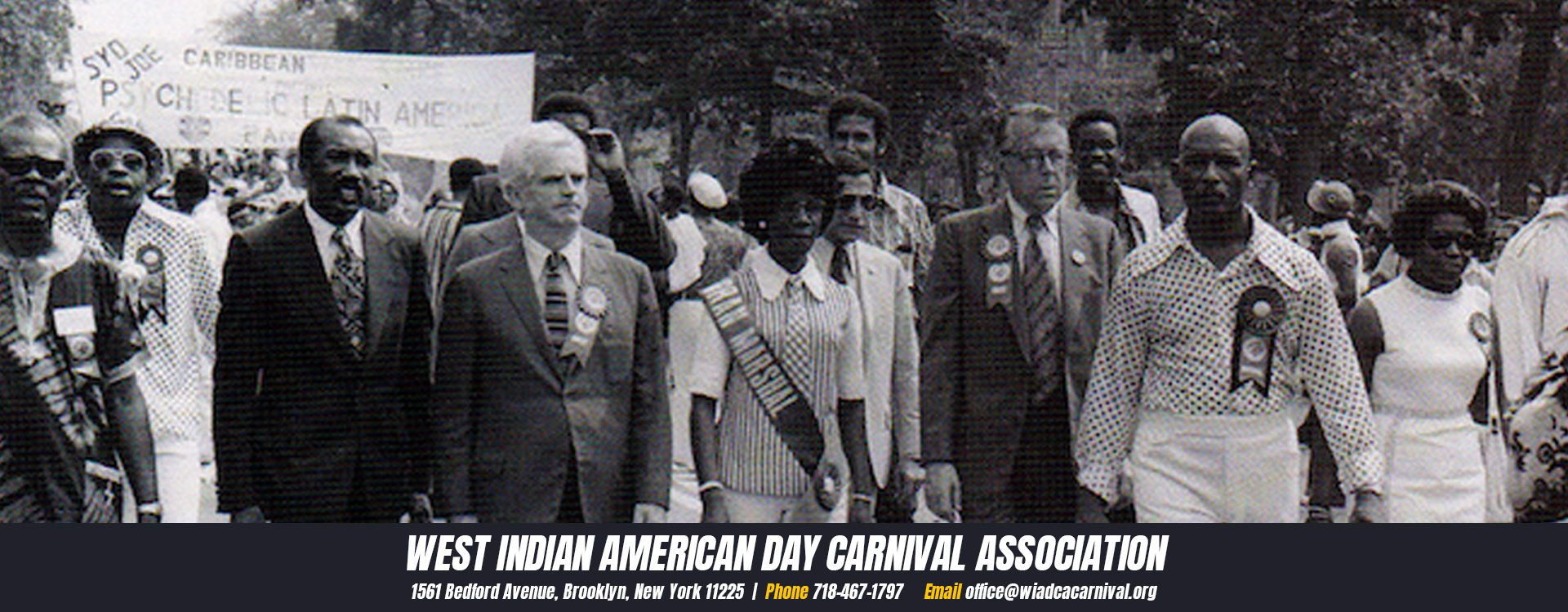

The Harlem permit was revoked in 1964 due to a violent riot. Five years later, a committee organized by Trinidadian Carlos Lezama obtained another permit for a parade on Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn. The parade has been held there ever since, beginning at Eastern Parkway and Utica Avenue and ending at Grand Army Plaza. Under the guidance of the West Indian American Day Carnival Association, the parade, now known as the West Indian Day Parade, has expanded and grown into one of the biggest parades of the New York City, attracting 4 million spectators and participants from around the world.

Costumes and, particularly, face masks are more elaborate every year at the West Indian Day Parade. Participants invest both money and time to come up with themes, costumes, and floats for the festivities. Face masks, which are often very large in size, come in a wide variety of styles inspired by natural and spiritual elements, mythical creatures, political events, and popular culture. The artistic and historical value of the parade cannot be denied and outstanding costumes are recognized with various prizes. Most importantly, though, the parade displays participants' pride in their country, heritage, and culture.

This entry was contributed by a Columbia University student enrolled in Art History W3897, African American Art in the 20th and 21st Centuries, taught by Professor Kellie Jones in 2008.